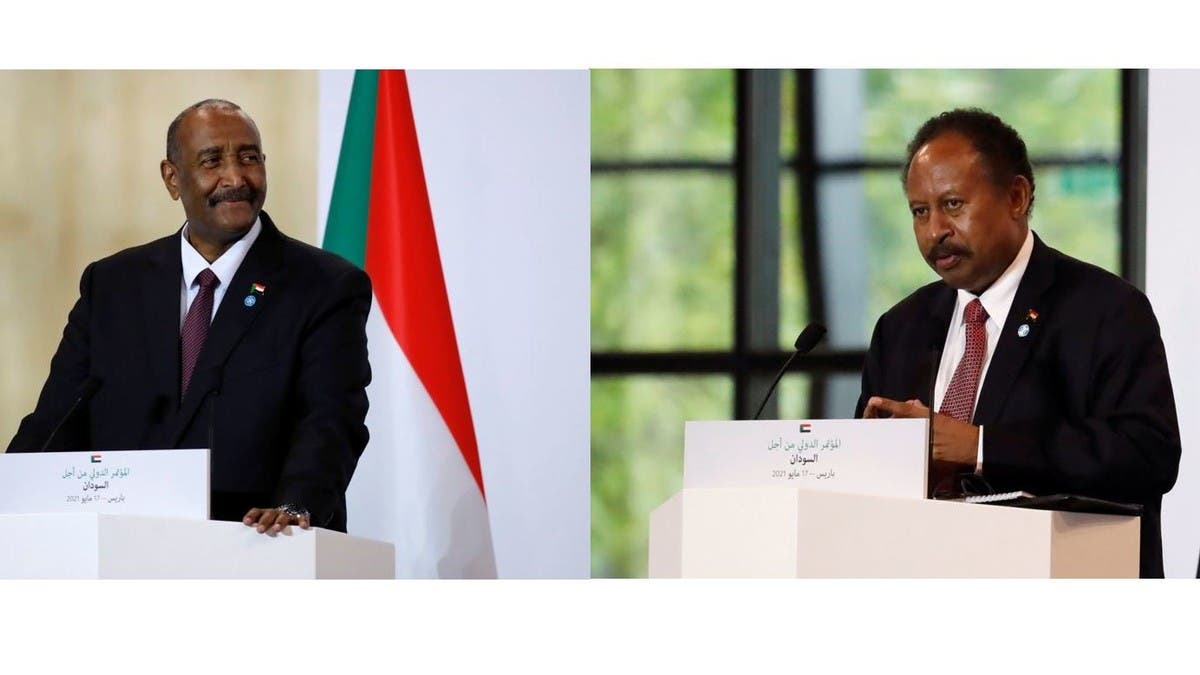

Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok’s resignation further plunged the country into a deeper political crisis and General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan may not be able to contain the ongoing protests, which calls for the country’s international allies to intervene, analysts told Al Arabiya English.

What happened?

Hamdok announced his resignation early Monday amid political deadlock and continuing protests against the October 25 military coup that derailed the country’s transition to democratic rule.

And even though Hamdok signed a political agreement with Burhan on November 21, saying he aimed to end the bloodshed of the clashes in the protests, many pro-democracy groups in Sudan opposed the deal and accused Hamdok of “betrayal” and “political suicide.”

The political agreement Hamdok and Burhan had signed stated that the PM was going to be allowed to form an independent cabinet of technocrats, until an election could be held in July 2023.

However, protests continued and clashes with security forces remained deadly. Medics reported that the number of deaths since the coup started rose to 56, while hundreds of others were wounded, in addition to reports of rape.

For two months since signing the deal with Burhan, Hamdok was unable to bridge the divide between the military’s demands and those of the pro-democracy groups who called for power to be handed over to a civilian government.

Hamdok said in his resignation address that he was “unable to combine all the components of the transition to reach a unified vision” and described the crisis in the country as essentially a political one, but that included aspects of the economy and social life.

Less than a day after Hamdok’s resignation General Abdel-Fattah Burhan stressed the need to form a government of independent competencies.

The general emphasized “the necessity of working to achieve the tasks of the transitional period, which is to achieve peace, establish security, address issues concerning people’s livelihoods and holding elections,” according to the state news agency SUNA.

He added: “Achieving those goals requires establishing cohesion of Sudan’s people in order to uphold the higher interests of the nation and staying away from partisan interests.”

Why did Hamdok resign?

Yezid Sayigh, Senior Fellow at Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center said: “Hamdok has found it impossible to address even the most basic urgent challenges of the economy and public finances – and of getting international aid and credit – within the restrictions set by Burhan and his allies.”

He added: “The scale and sustained nature of public resistance to the coup has been strong enough to prompt Hamdok to revise his assessment of the utility or feasibility of maintaining the agreement with Burhan.”

Nevertheless, Sayigh believes that Hamdok's calculus may add up to having Burhan reach out to him again as a last resort.

“Hamdok may have calculated that he could gain greater leverage by resigning, in the expectation that Burhan will have to come back to him to form a government yet again, because he has no genuinely viable alternatives to Hamdok,” Sayigh said.

However, Theodore Murphy, Director of the Africa Program at the European Council on Foreign Relations disagrees with that assessment. He believes it’s no longer a given that Burhan has the upper hand in terms of power.

He also added that Hamdok had lost credibility in the streets of Sudan, therefore “returning him to power would not serve the purpose of quieting the [protests].”

What can we expect for Sudan’s future?

Sudan is in a very fragile state right now, suffering from an ailing economy, widespread shortages of essential goods such as fuel, bread and medicine, incredibly high inflation and a society that was hard hit by the coronavirus outbreak.

The political future of the country is up in the air. Many wonder who could be the right individual to find the balanced compromise between the military, the protesters in the street and the pro-democracy movement, to map out a plan for Sudan’s future.

Murphy said: “Without Hamdok there [is] no clear interlocutor but rather a cacophonous mixture of civilian political and protest movement voices that the diplomatic community could poorly navigate.”

He also added: “The Political Agreement rested solely on Hamdok (the only civilian signatory). Without him the Agreement is dead, and moreover the last vestige of the civilian component of the transitional government as well. Preferring something imperfect, rather than nothing and the unknown, the current situation is daunting.”

But hope for Sudan is not dead yet, so long as it gets assistance form international partners.

“Finding a new way forward requires more of Sudan’s international partners than supporting the flawed Political Agreement would have,” Murphy said. ”But it can ultimately lead to a more solid, durable, foundation for Sudan’s democratic transition than the increasingly shaky edifice it rested upon of late.”

For the latest headlines, follow our Google News channel online or via the app.

Read more:

Sudan PM’s decision to resign throws country further into the abyss

Sudan’s PM announces resignation amid political deadlock

Sudan security forces kill two anti-coup protesters: Medics

US calls for civilian rule in Sudan after Hamdok quits as premierT

World3 years ago

World3 years ago

World3 years ago

World3 years ago

Business11 months ago

Business11 months ago

Entertainment7 years ago

Entertainment7 years ago

World7 years ago

World7 years ago

Entertainment7 years ago

Entertainment7 years ago